In this article, we'll explore joints—how they're classified, structured, and what makes them stable.

What is a Joint?

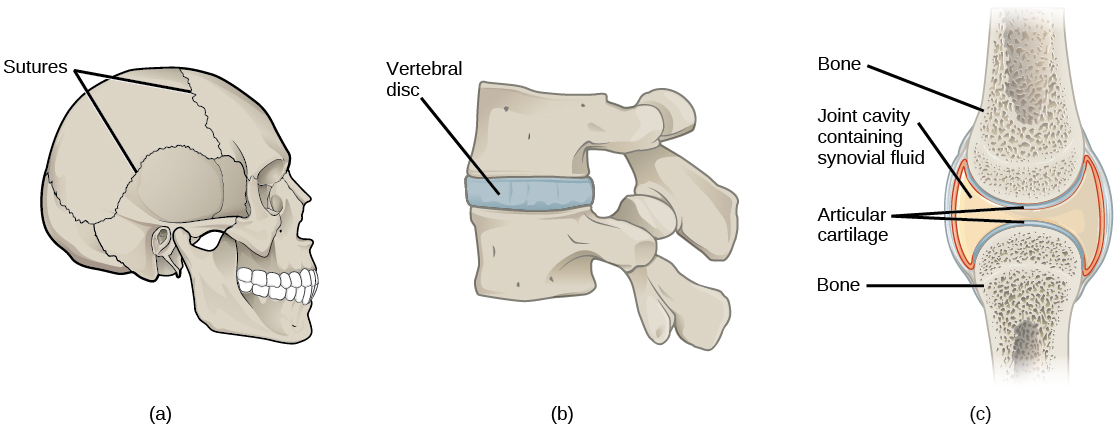

A joint, or articulation, is the connection between two bones in your body. Joints are broadly classified based on the type of tissue that connects the bones. There are three main types of joints:

- Fibrous Joints: These joints are connected by fibrous tissue, making them very strong and generally immovable. A good example is the sutures in the skull, where bones are tightly joined.

- Cartilaginous Joints: In these joints, bones are connected by cartilage. Typically, the bones are covered with hyaline cartilage and joined by a wedge of fibrocartilage. An example is the joints between vertebrae in the spine.

- Synovial Joints: These are the most common and most movable type of joints. They are filled with synovial fluid and enclosed in a fibrous capsule. This fluid lubricates the joint, absorbs shocks, and distributes nutrients. Synovial joints are further subdivided into several types, each allowing different kinds of movement.

Classification of Joints:

1. Classification by Type of Tissue

- Fibrous Joints: Bones are connected by fibrous tissue, providing strength and stability but little to no movement.

- Cartilaginous Joints: Bones are connected by cartilage, allowing for slight movement.

- Synovial Joints: Bones have articulating surfaces enclosed within a fluid-filled joint capsule, permitting free movement.

2. Classification by Degree of Movement

- Synarthrosis: Immovable joints.

- Amphiarthrosis: Slightly movable joints.

- Diarthrosis: Freely movable joints.

Fibrous Joints

Fibrous joints are bound by tough, fibrous tissue, prioritizing strength and stability over movement. They can be further classified into:

- Sutures: Immovable joints found only between the flat bones of the skull. These joints allow slight movement during birth, enabling the skull to deform as it passes through the birth canal, and become immobile by age 20.

- Gomphoses: Immovable joints where the teeth articulate with their sockets in the maxilla or mandible. The teeth are held in place by the strong periodontal ligament.

- Syndesmoses: Slightly movable joints where bones are connected by an interosseous membrane, such as the middle radioulnar and middle tibiofibular joints.

Cartilaginous Joints

Cartilaginous joints unite bones with fibrocartilage or hyaline cartilage. They come in two main types:

- Synchondroses: Bones connected by hyaline cartilage, allowing no movement (synarthrosis). An example is the joint between the diaphysis and epiphysis of a growing long bone.

- Symphyses: Bones united by a layer of fibrocartilage, allowing slight movement (amphiarthrosis). Examples include the pubic symphysis and the joints between vertebral bodies.

Synovial Joints

Synovial joints are the most common type of joint, characterized by a fluid-filled joint cavity within a fibrous capsule. These freely movable joints (diarthrosis) can be further sub-classified based on the shape of their articular surfaces and the types of movements they allow:

- Hinge Joints: Permit movement in one plane, usually flexion and extension (e.g., elbow, ankle, knee).

- Saddle Joints: Have articular surfaces with a reciprocal concave-convex shape, resembling a saddle (e.g., carpometacarpal joints).

- Plane Joints: Have relatively flat articular surfaces, allowing bones to glide over one another (e.g., acromioclavicular joint, subtalar joint).

- Pivot Joints: Allow for rotation only, formed by a central bony pivot surrounded by a bony-ligamentous ring (e.g., proximal and distal radioulnar joints, atlantoaxial joint).

- Condyloid Joints: Contain a convex surface articulating with a concave elliptical cavity, also known as ellipsoid joints (e.g., wrist joint, metacarpophalangeal joints).

- Ball and Socket Joints: Feature a ball-shaped surface of one bone fitting into a cup-like depression of another, permitting movement in multiple axes (e.g., hip joint, shoulder joint).

Structures of a Synovial Joint

Key Structures of a Synovial Joint

Articular Capsule- Fibrous Layer (Outer): Made of white fibrous tissue, this layer holds the bones together and supports the underlying synovium.

- Synovial Layer (Inner): A highly vascularized layer of serous connective tissue, known as the synovium, which absorbs and secretes synovial fluid and mediates nutrient exchange between the blood and joint.

- Covers the articulating surfaces of bones in the joint.

- Functions: Minimizes friction during movement and absorbs shock.

- Found within the joint cavity.

- Functions: Lubrication, nutrient distribution, and shock absorption.

- Articular cartilage relies on the diffusion of nutrients from this fluid due to its avascular nature.

Accessory Structures of a Synovial Joint

Accessory Ligaments- Bundles of dense regular connective tissue that resist strain and protect the joint from extreme movements.

- Small sacs lined with synovial membrane and filled with synovial fluid.

- Functions: Reduce friction at key points in the joint, enhancing movement freedom and protecting articular surfaces from degeneration.

Innervation

- Synovial joints are richly supplied by articular nerves, which also supply the muscles moving the joint and the skin covering their distal attachments.

- Functions of Articular Nerves: Transmit proprioceptive (joint position) and nociceptive (pain) sensations.

Vasculature

- Arterial Supply: Provided by articular arteries, arising from vessels around the joint and located mainly in the synovial membrane.

- Venous Drainage: Articular veins accompany the arteries, also found in the synovial membrane.

- Anastomoses: Frequent connections between arteries ensure a continuous blood supply regardless of joint position.

Clinical Relevance

Osteoarthritis

- Definition: The most common form of joint inflammation, resulting from prolonged use of joints.

- Pathophysiology: Wearing away of articular cartilage and erosion of underlying bone surfaces.

- Symptoms: Joint pain, stiffness, and discomfort due to reduced effectiveness of cartilage and roughened bone edges.

- Commonly Affected Joints: Weight-bearing joints like hips and knees.

- Other Causes of Arthritis:

- Infectious Arthritis: Due to bacterial infection entering the joint cavity.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: An autoinflammatory condition.

- Reactive Arthritis: Inflammation caused by infection elsewhere in the body, not directly involving the joint.

Joint Stability

The stability of joints is crucial in understanding why some joints are more prone to dislocation and injury than others. This also forms the basis for treating joint injuries. In this article, we will explore the various factors that contribute to joint stability.

Three main factors contribute to the stability of a joint:

- The Articulation: The way the bones fit together. A more stable joint has more surface area of one bone articulating with the corresponding surface of the other bone.

- Ligaments: Strong bands of tissue that connect bones and help stabilize the joint.

- Muscle Tone: The tension in the muscles surrounding the joint.

For example, the shoulder joint is less stable because it has a wide range of motion. To compensate, it has a cartilaginous rim called the labrum that deepens the socket and helps stabilize the joint between the humerus and scapula.

Factors Contributing to Joint Stability

Shape, Size, and Arrangement of Articular Surfaces- The shape and size of the articulating surfaces are key in determining joint stability.

- For instance, the shoulder joint is less stable because the humeral head is much larger than the glenoid fossa of the scapula, resulting in less contact between the bones.

- In contrast, the hip joint is more stable because the acetabulum of the pelvis fully encompasses the femoral head, providing a snug fit. However, this stability comes at the cost of reduced range of movement compared to the shoulder.

Ligaments

- Ligaments prevent excessive movement that could damage the joint.

- The more ligaments a joint has, and the tighter they are, the more stable the joint becomes.

- However, tighter ligaments also restrict movement, illustrating the trade-off between stability and mobility.

- Ligaments can stretch, tear, or damage the bone they attach to if subjected to disproportionate or repeated stress, making sportspeople particularly susceptible to ligament injuries.

Tone of Surrounding Muscles

- Muscle tone around a joint greatly enhances its stability.

- For example, the rotator cuff muscles support the shoulder joint by keeping the humeral head in the shallow glenoid cavity of the scapula.

- Loss of muscle tone, as seen in old age or after a stroke, can lead to dislocation. Dislocated shoulders can tear the rotator cuff muscles, making future dislocations more likely.

- Similarly, muscle tone around the knee is crucial for its stability. Imbalanced or inappropriate training can make the knee prone to injury and lead to chronic pain.

2 Comments

so helpful! thank you

ReplyDeletePleasure!!

Delete